Torres Strait Islander Religion

Religious Beliefs. Indigenous religion in the Torres Strait fell victim to Christianity early and thoroughly in the years of European contact, and few traces of it remain. It appears that beliefs focused upon a cast of culture heroes whose travels throughout the region were recounted in creation myths. Through the exploits of these mythological beings the physical features of the islands and many of the social and cultural practices of the islanders were brought into being. Principal among these culture heroes, at least in the Western Islands, was Kwoiam, said to have come from the Aboriginal peoples of Cape York, whose deeds were recounted on important ceremonial occasions. Culture heroes, the things they used, and the places with which they were associated assumed a totemic character in the beliefs of the islanders, and a variety of hero cults existed throughout the islands. There is some evidence to suggest that the hero cults are an importation from Aboriginal and Papuan sources and that they were grafted onto an earlier belief system, which itself was totemic in nature. Christianity was first introduced through the efforts of the London Missionary Society in the late 1700s; this creed was replaced by Anglicanism when the society withdrew from the strait in 1914. In the 1930s, Pentecostalism was introduced by islanders returning from Queensland communities and established a rivalry with Anglicanism for island followers. Island Christianity today incorporates much precontact Religious practice, and recourse to magic (for gardening, fishing, revenge, and curing) still occurs.

Religious Practitioners. Traditionally medicine men, or magicians, began training in their early teens by becoming apprenticed to an established practitioner. Training involved Direct teaching, practice, and submission to trials by ritual ordeal. The apprentice attained full practitioner status when he successfully cast a "hostile" spell—that is, when he succeeded in causing the death of an intended victim through magic. Traditional officiants at ceremonial occasions are elder men of high repute and esteem within their villages, for these are the people in whom resides the greatest knowledge of and experience in cult lore, practice, and magic. Islander men have been trained to the ministry and priesthood since the early days of proselytizing in the region.

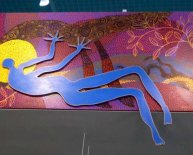

Ceremonies. The principal island ritual occasion is the "tombstone opening, " wherein the grave marker is formally revealed to all kin and friends of the deceased; this ceremony may take place many years after the actual death. This ritual is an occasion of feasting and dancing and may bring in celebrants from throughout the strait as well as from the mainland. Other major ceremonial occasions follow the Christian calendar and include Christmas and Lent. Of particular importance is the 1 July celebration, commemorating the date of the arrival of "The Light"—that is, the arrival of the first mission teachers sent by the London Missionary Society. Celebrations involve feasting, dancing, and singing. Traditional hero-cult ceremonials occurred in the context of initiation rites and involved the reenactment of important events in the hero myths. Ceremonial costume included elaborate sacred masks.

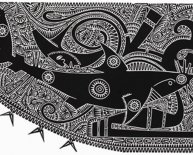

Arts. In traditional times, masks, headdresses, and articles of personal adornment attained a high degree of decorative elaboration. Islander canoes were highly carved. Current Musical instruments include drums, panpipes, whistles, flutes, and rattles, and the composition and performance of songs for festive occasions is still a highly valued skill. Island dance is a dramatic, coordinated series of stamping and leaps performed by troupes of young men, often in competition with one another.

Medicine. Traditional medicine involved the use of magic, either alone or in conjunction with herbal remedies or bloodletting. The type of cure employed was dependent upon diagnosis of visible symptoms. Today, islanders may make use of Western medicine but still respect traditional curing practices.

Death and Afterlife. Traditional beliefs held that the spirit of the deceased was capable of bringing harm to the community, and funerary ritual was intended to avert such danger through appeasing the spirit and freeing it to make the journey to an "Isle of the Dead" somewhere in the west. When a man died, the village members marked the occurrence with loud wailing and crying, then abandoned the Village site to the corpse and the male kin of the widow, who built a platform upon which the body was placed. At a later date, the head of the corpse would be removed for use in Ritual divination to learn if sorcery was the cause of death and thus to determine the necessity of mounting a revenge party. The widow kept the skull to carry about with her throughout her mourning period, but the remainder of the corpse would be interred. Current funerary practice follows customary Western standards, although a tombstone-opening festival, featuring traditional feasting and dancing, is later held.