Indigenous Spirituality

We see your skin as a coat of armour, protecting your spirit and your Dreaming.—Rob Waters [1]

Lack of respect for spiritual protocols

Some non-Aboriginal people are unable to respect Aboriginal spirituality once their own interests are threatened.

Lake Eyre in South Australia is sacred to the local Arabana people. In 2011 they had banned sailing on the lake due to its spiritual significance.

When the lake flooded after a long period of drought the Lake Eyre yachting club’s commodore was quick to assert that the sailors had “a perfect common law right to boat on that waterway” [2], encouraging them to to risk hefty fines for using the lake without a permit in defiance of Arabana wishes.

Aboriginal women in Australia know they should not play the yidaki (didgeridoo) because it can make them infertile or cause multiple births [3]. This didn’t stop publisher Harper Collins from including a chapter on ‘How to play a didgeridoo’ in The Daring Book for Girls, targeted also for the Australian market.

Academic and Aboriginal education advocate Dr Mark Rose said he “wouldn’t let my daughter touch one [didgeridoo]. I reckon it’s the equivalent of encouraging someone to play with razor blades.” Harper Collins refused calls to pulp the book, saying that there was no “genuine reason” and the company was not convinced they had “offended all Australian Aborigines” [3].

Spiritual tourism

A high number of tourists to Australia want to interact with Aboriginal people and learn about their culture. This seems to match with what Aboriginal people want—the tourist industry is what they feel is compatible with their cultural, economic and social goals [4].

Aboriginal spirituality is high on the list of many tourists visiting Australia, so much so, that some propose to take local traditional tourism to another level and promote it as spiritual tourism to teach people about the spirituality of the region [5].

“A spiritual tourist is a person who travels as a tourist for spiritual growth or development, without overt religious compulsions, ” says Farooq Haq, a business lecturer at Charles Darwin University [6].

But a venture in the tourism industry is not without risk. Aboriginal communities need to be mindful not to create programs that miss their target or develop programs in areas that are inaccessible to tourists.

Tourism is a good way to [pass on cultural knowledge] and it helps to build pride in our young people and helps them to have confidence when talking with whitefellas. —Dillon Andrews, Bungoolee Aboriginal Tours, Fitzroy Crossing, Western Australia [4]

Homelands harbour a ceremonial ‘economy’

Aboriginal ceremonies can be considered an ‘economy’, according to a senior ceremonial leader. They are hard work that contributes to the richness of Aboriginal culture.

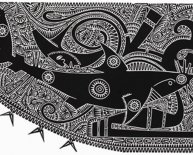

Senior ceremonial leader and leader of the Yolngu Madarrpa clan, Djambawa Marawili, of North East Arnhem Land, sees cultural ceremonies as an economy because they contribute to the richness of his culture. The ceremonial economy includes funeral ceremonies, initiation of the young and ceremonies of the traditional Yolngu parliament (njärra), the latter is sadly no longer practised. Some ceremonies have lost their cultural significance and are only shown at festivals, such as Garma. [7]

Whole families accompany those involved in ceremonies but don’t participate in them. Ceremonies bring people together and create strong connections. They are considered “a real job” in the communities on homelands.

The ceremonial economy seems to occur in Arnhem land on many days of the month. Song men are doing certain ceremonies for 20 days each month since the year 2000. [7]