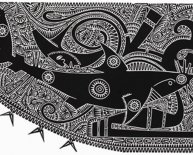

Indigenous, Aboriginal

In a field of complex and contentious issues, understanding Aboriginal identity in Canada is one of the most challenging tasks. Perceptions of Aboriginal identity can be complex. Definitions may have legal implications that often operate in surprising ways. In this section, we go over the various ways in which Aboriginal peoples in Canada self-identify and are defined by the stateand the ways in which these two systems of definition, one based in law and legislation, the other in family tradition and community practice, are frequently in conflict.

Terminology

For many people who live in traditional communities or who have deep and clear roots within them, identity can be, at least in some ways, straightforward. They identify themselves within a particular family, clan, band, or nation and may prefer to use the traditional terms and names that locate them within those circumstances. When introducing themselves, people may identify themselves by their genealogy, noting parents, grandparents, and more distant ancestors, by clan, or by the traditional name of their community or nation. Those identifications, however, often have deeper dimensions and reflect a strong and spiritual connection to the land and other cultural traditions.

Identification based on connection to land and territory can become very difficult, however, for communities who have lost their land base, as, for instance, many tribes in the US did in the 1950s under a government policy known as Termination, or might have in Canada under the Trudeaus proposed White Paper policies. These forms of identification may also become complex when people leave their ancestral communities or are born in cities or other locations. In some cases, their right to claim membership may be challenged. In the United States, tribal communities decide membership and the standards of inclusion vary widely. In Canada, while the government decides Indian status (see below), community acknowledgment is also a critical factor in determining personal identity, even when legal status is denied.

It is possible that people less familiar with the specific context of their community may not recognize the traditional community name, or might know the community or nation by another name than the one the community uses: many common names others use for Aboriginal communities and nations derive from terms used by other nations or groups (e.g., Sioux is commonly used for Dakota people, although it is thought to derive from a pejorative term used by Anishinaabe neighbors with whom they were historically in conflict), or used by Europeans (e.g, Nootka for Nuu-chah-nulth people, a name thought to derive from the European misapplication of a place term in the Nuu-chah-hulth language).