Australians Aborigines

The forest provides for Bronwyn Munyarryun, who strips off the soft sheathing of a paperbark tree to fashion a bed to be used in a healing ceremony. She lives on the monsoon-swept fringe of Arnhem Land.

The forest provides for Bronwyn Munyarryun, who strips off the soft sheathing of a paperbark tree to fashion a bed to be used in a healing ceremony. She lives on the monsoon-swept fringe of Arnhem Land.

The Anangu of central Australia call the iconic sandstone monolith Uluru. They believe it was created by their ancestral beings. Europeans dubbed it Ayers Rock in 1873, but the name was changed back to Uluru in 1985.

Entrails of a green sea turtle will be cooked and eaten during a feast in the Bawaka homeland. The turtle is a protected species, but Aboriginals are permitted to hunt it as a traditional staple food. The turtle figures prominently in Songlines—the routes of creatures during Dreamtime, the era in Aboriginal belief when totemic beings created the Earth.

Representing supernatural beings, boys daubed in white clay prepare to take part in the opening ceremonies of the Garma Festival, a Yolngu cultural event in Gulkula. In Aboriginal culture white body paint also signifies mourning.

Representing supernatural beings, boys daubed in white clay prepare to take part in the opening ceremonies of the Garma Festival, a Yolngu cultural event in Gulkula. In Aboriginal culture white body paint also signifies mourning.

Nellie Gupumbu (left) and Lisa Garraynjarranga camp along the Arafura Sea with their grandmother, Lily Gurambara. Remote doesn’t mean out of touch for Gurambara, who works the phone to arrange community events.

At the Garma Festival in Gulkula, Yolngu women massage a visitor with oils and herbs. The annual event attracts tourists eager to experiment with Aboriginal rituals.

Heedless of timetables and routines, an Aboriginal child is rounded up for school by the principal in Watarru. Indigenous dropout rates exceed 60 percent in remote areas.

Heedless of timetables and routines, an Aboriginal child is rounded up for school by the principal in Watarru. Indigenous dropout rates exceed 60 percent in remote areas.

Fire is a tool, a gift, and a possible danger, which Anangu children learn at an early age in Watarru, one of many Aboriginal homelands where tradition still lights the way.

Flames painted on arms and chests, Bronwyn Jimmy (left) and Tinpulya Mervin of Watarru perform a fire dance in the Great Victoria Desert, a rite for women only. Aboriginals set fires to clear the land of underbrush.

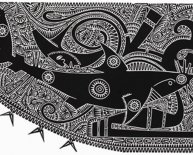

Men in Maningrida decorate a log coffin they will use to bury the skull of an ancestor. The skull, housed until recently in a museum in Darwin, had just been returned to the community.

A Djinang boy in Gatji is painted with the totemic figure of the catfish to celebrate the homecoming of an ancestor’s remains. Since 1990 the remains of more than 1, 100 Aboriginals have been repatriated to Australia.

Aboriginals in touch with the land see desert oaks and imagine the drinking water in the trees’ cavities. They see a full moon above Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park and find light for a nocturnal event.