Native tribes in Australia

Two new research studies, published in two separate scientific journals, have found that the DNA of certain Amazonian Indian tribes are similar to those of the indigenous inhabitants of Australia and Melanesia. However, as often happens in genetic studies of American Indians, the two research groups offered sharply contrasting interpretations of what this data means for how the Americas were first peopled.

Two new research studies, published in two separate scientific journals, have found that the DNA of certain Amazonian Indian tribes are similar to those of the indigenous inhabitants of Australia and Melanesia. However, as often happens in genetic studies of American Indians, the two research groups offered sharply contrasting interpretations of what this data means for how the Americas were first peopled.

The suggestion that peoples from Oceania had at one time populated the Americas is not new and recent genetic studies now largely confirm admixture between Polynesians and Native Americans before European contact. Moreover, some ancient skeletons from South America have been found to have similar appearances to indigenous Australians, leading a few to speculate that there had been ancient contact.

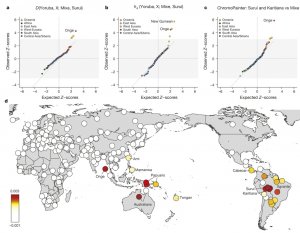

Pontus Skoglund, a post-doctoral researcher at the Harvard Medical School who co-authored the study published in Nature on July 21, “Genetic Evidence for Two Founding Populations of the Americas, ” noted the similarities between ancient Australian and American Indian skeletons had never been taken seriously because, “there has always been this question of how statistically informative this morphology [the study of structures such as skeletons] is, and to what extent this actually reflects population relationships.” So the group was surprised to find traces of genetic markers among some South American Indians that were “more closely related to indigenous Australians, New Guineans and Andaman Islanders than to any present-day Eurasians or Native Americans.”

“I think almost no geneticists would have expected this, ” Skoglund says. “What it tells us in terms of history, which is more important, is that there was a greater diversity of Native American ancestral populations than people previously thought.” The strongest relationship is between certain Amazonian tribes, such as the Karitiana, Surui, and Xavante, and the Indigenous Peoples of Papua New Guinea, two regions that are coincidentally among the most linguistically diverse in the world. According to the Harvard study, the date when this genetic mixing occurred is so old that the two groups may have split off before the populating of Australia, more than 40, 000 years ago. But this admixture is only found in certain South American Indians, and not at all in North American Indians.

“This suggests that there is an ancestral population that crossed into the Americas that is different from the population that gave rise to the great majority of Americans. And that was a great surprise, ” says study co-author David Reich, a geneticist at Harvard University. The Harvard team named this mysterious ancestral group, “Population Y, ” from the word Ypykuéra, meaning ancestor in Tupí, the language spoken by the Surui and Karitiana. How and when these ancestors migrated to the Americas, the Harvard team does not attempt to determine based upon their data. Skoglund speculates that “there were perhaps multiple pulses of people into the Americas, and they had slightly different proportions of this ancestry. But which of the pulses came first and which different routes they took, we just don’t know.”

A far more different interpretation of this and other genetic data comes from the study in the journal Science, published on July 22, entitled “Genomic Evidence for the Pleistocene and Recent Population History of Native Americans.” Led by scientists from the Center for Geogenetics at the University of Copenhagen and the University of California, Berkley, this team also found traces of Australasian ancestry in some South American natives, although it was not as strong as that reported by the Harvard team in . The study in Science had a greater scope, according to Maanasa Raghavan, a molecular biologist in Copenhagen and co-author of the report, with the goal to “bring together genomic, archaeological and other research on modern and ancient peoples of the Americas to come up with a clearer picture of how the continents were populated.”

According to the Copenhagen/Berkley team, “the ancestors of all present-day Native Americans, including Athabascans and Amerindians, entered the Americas as a single migration wave from Siberia no earlier than 23 thousand years ago (KYA), and after no more than 8, 000-year isolation period in Beringia. Following their arrival to the Americas, ancestral Native Americans diversified into two basal genetic branches around 13 KYA, one that is now dispersed across North and South America and the other is restricted to North America.”

Of course the idea put forward by the scientists from Copenhagen and Berkley, that all American Indians are descended from one ancestral group, directly contradicted the conclusions of the Harvard study, whose authors were quick to react. Reich countered on the BBC that, “both studies show that there have been multiple pulses of migration into the Americas” and in Smithsonian Magazine that “there’s another early population that founded modern Native American populations.”

Furthermore, to somehow account for the Oceanic genes found in South American Indians, Rasmus Nielsen, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley and one of the authors of the study in Science suggested that, “the relationship between Native Americans and Australasians could be the result of Alaskan populations that are genetically closer to Australasians, such as the Aleutian Islanders.” Reich dismissed this possibility. “I think that’s very weak—it’s very, very speculative, ” adding that the one-migration model is “not a clear alternative, ” because it would have left genetic clues in the migration from north to south; “We have overwhelming evidence of two founding populations in the Americas.”

Critics of the Science study also noted that the small sample size used make the study’s conclusions less persuasive, an argument scoffed at by Nielsen, who defended his teams scholarship, “It’s nothing about the sample; it’s all in the interpretation.” And in the end he is right. Vastly divergent interpretations from genetic studies regarding the settlement of the Americas are actually the norm, as the genetic data can only offer clues, but cannot provide answers. Maybe those answers will be forthcoming in the future, but right now, it is clearly anybody’s guess.