Native population of Australia

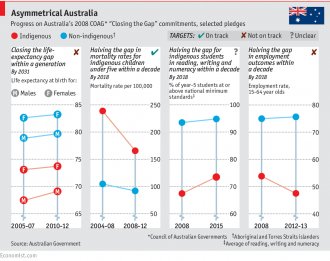

THE massive gulf in living standards between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians has long been one of the country’s great shames. After much pressure from activists, governments have channelled increasing amounts of money and political will in an effort to “close the gap”. But a new report released on February 10th acts as a depressing record of the past eight years of policymaking, and an indication of how little progress has been made. It provides an update on the seven pledges made in 2008 by the Coalition of Australian Governments (COAG) to reduce racial inequality. Just two targets are on track to be met: the commitment to halve the gap between the indigenous and non-indigenous mortality rate of children under five (which started from an appalling baseline), and the aim to increase the number of indigenous students completing high school.

THE massive gulf in living standards between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians has long been one of the country’s great shames. After much pressure from activists, governments have channelled increasing amounts of money and political will in an effort to “close the gap”. But a new report released on February 10th acts as a depressing record of the past eight years of policymaking, and an indication of how little progress has been made. It provides an update on the seven pledges made in 2008 by the Coalition of Australian Governments (COAG) to reduce racial inequality. Just two targets are on track to be met: the commitment to halve the gap between the indigenous and non-indigenous mortality rate of children under five (which started from an appalling baseline), and the aim to increase the number of indigenous students completing high school.

What little positive reading there is ends with that. Despite another goal to halve the employment gap, the indigenous employment rate has actually decreased since 2008, while the non-indigenous rate has gone up. This is partly due to the Global Financial Crisis, which disproportionately affected under-educated men (who make up 50% of indigenous men with jobs). A new target for improving access to early-childhood education, after the previous target expired (unmet) in 2013, is headed nowhere. Levels of reading and numeracy have crept up marginally, but not enough.

This is partly due to the Global Financial Crisis, which disproportionately affected under-educated men (who make up 50% of indigenous men with jobs). A new target for improving access to early-childhood education, after the previous target expired (unmet) in 2013, is headed nowhere. Levels of reading and numeracy have crept up marginally, but not enough.

Most damning of all is the lack of progress on life expectancy: indigenous Australians will die a decade earlier than non-indigenous Australians. The likelihood of closing this gap within a generation—the government’s headline target—appears remote. Indigenous life expectancy is rising, but only at the same rate as the total population’s. The gap in the mortality rate for most chronic diseases is falling, but for cancer the rate is widening. A decrease in the indigenous smoking rate will eventually bear fruit in future reports.