Australian Aboriginal beliefs

Notwithstanding the diversity of Australian Aboriginal beliefs, all such peoples have had similar concerns and questions about death: What should be done with the body? What happens to the soul? How should people deal with any disrupted social relationships? And how does life itself go on in the face of death? All of these concerns pertain to a cosmological framework known in English as "The Dreaming" or "The Dreamtime, " a variable mythological concept that different groups have combined in various ways with Christianity.

There are many different myths telling of the origins and consequences of death throughout Aboriginal Australia and versions of the biblical story of the Garden of Eden must now be counted among them. Even some of the very early accounts of classical Aboriginal religion probably unwittingly described mythologies that had incorporated Christian themes.

There are many traditional methods of dealing with corpses, including burial, cremation, exposure on tree platforms, interment inside a tree or hollow log, mummification, and cannibalism (although evidence for the latter is hotly disputed). Some funeral rites incorporate more than one type of disposal. The rites are designed to mark stages in the separation of body and spirit.

Aboriginal people believe in multiple human souls, which fall into two broad categories: one is comparable to the Western ego—a self-created, autonomous agency that accompanies the body and constitutes the person's identity; and another that comes from "The Dreaming" and/or from God. The latter emerges from ancestral totemic

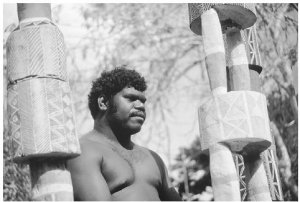

An Aborigine from the Tiwi tribe in Bathurst, New South Wales, Australia, stands beside painted funeral totems. Phases of funerary rites are often explicitly devoted to symbolic acts that send ancestral spirits back to their places of origin where they assume responsibility for the wellbeing of the world they have left behind .

An Aborigine from the Tiwi tribe in Bathurst, New South Wales, Australia, stands beside painted funeral totems. Phases of funerary rites are often explicitly devoted to symbolic acts that send ancestral spirits back to their places of origin where they assume responsibility for the wellbeing of the world they have left behind .

CHARLES AND JOSETTE LENARS/CORBIS

sites in the environment, and its power enters people to animate them at various stages of their lives.At death, the two types of soul have different trajectories and fates. The egoic soul initially becomes a dangerous ghost that remains near the deceased's body and property. It eventually passes into nonexistence, either by dissolution or by travel to a distant place of no consequence for the living. Its absence is often marked by destruction or abandonment of the deceased's property and a long-term ban on the use of the deceased person's name by the living. Ancestral souls, however, are eternal. They return to the environment and to the sites and ritual paraphernalia associated with specific totemic beings and/or with God.

The funerary rites that enact these transitions are often called (in English translation) "sorry business." They occur in Aboriginal camps and houses, as well as in Christian churches because the varied funerary practices of the past have been almost exclusively displaced by Christian burial. However, the underlying themes of the classical cosmology persist in many areas. The smoking, (a process in which smoke, usually from burning leaves, is allowed to waft over the deceased's property) stylized wailing, and self-inflicted violence are three common components of sorry business, forming part of a broader complex of social-psychological adjustment to loss that also includes anger and suspicion of the intentions of persons who might have caused the death. People may be held responsible for untimely deaths even if the suspected means of dispatch was not violence but accident or sorcery. The forms of justice meted out to such suspects include banishment, corporal punishment, and death (even though the latter is now banned by Australian law).

See also: How Death Came INTO THE World ; Suicide Influences AND Factors: Indigenous Populations

Bibliography

Berndt, Ronald M., and Catherine H. Berndt. The World of the First Australians: Aboriginal Traditional Life: Past and Present . Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 1988.

Elkin, A. P. The Australian Aborigines: How to Understand Them , 4th edition. Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1970.

Maddock, Kenneth. The Australian Aborigines: A Portrait of Their Society . Ringwood: Penguin, 1972.

Swain, Tony. A Place for Strangers: Towards a History of Australian Aboriginal Being . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.